I compiled a list of my favorite films of the year for Yerevan Magazine.

These are films that have made a lasting impression on me, and I hope, will leave an impression on you as well.

I need to make some guidelines clear. These are all films that have been released in theaters in 2011, whether domestically or internationally. If a film was released in theaters in 2010 (in France, for instance), but wasn’t released in the United States until 2011, I will consider such a film ineligible. If a film, however, screened solely in film festivals in 2010, but received its official release in theaters in 2011, then such a film is eligible. This is a personal preference, but one that acknowledges the actual release dates of films.

I have seen more new film releases this year (over 40) than any previous year, which, of course, makes putting together a top ten list of favorite films that much harder. This list of films will eventually change, because my feelings toward all these films are still in flux, also because I still haven’t seen several films (primarily foreign films) because they haven’t been released in the United States.

This, however, is a list of my favorite films as of the end of the actual year itself. So, without further ado, this is a top ten list of my favorite films of 2011.

1.

The Tree of Life

The film of the year comes in the form of a lyrical meditation on life, a film that transcends narrative storytelling and instead structures itself as a cinematic poem. The Tree of Life, in some sense, can be defined as post-cinematic in its disregard for a conventional narrative structure. The film isn’t so much concerned with story, as it is concerned with emotion as a guiding force. Terrence Malick represents a fractured state of memory with his use of images, and his constantly moving, always sweeping camera, exemplifies the passing of time. There is no other film that was as ambitious this year, both in content and form, and there was no other filmmaker that was as masterful.

2. Drive

Nicolas Winding Refn’s film is filled with references to

Le Samouraï,

Bullitt and

Miami Vice. The Driver (Ryan Gosling) is a silent soul, roaming the streets of Los Angeles as he moonlights as a getaway driver. The filmmaker incorporates slow motion, operatic music, beautiful dissolves, as well as exaggerated and over-the-top violence. The film is extremely patient, and despite being an action thriller, the filmmaker works against most of the conventions of the genre. There isn’t much The Driver says, but that’s because his character relies on Ryan Gosling’s performance; he speaks with his eyes, and trust me, he’s saying a lot, whether you’re listening or not. The soundtrack to the film is one of the most popular soundtracks in recent years, and the film itself is stylish and retro, and feels like a product of the 1980s.

3.

Meek’s Cutoff

Meek’s Cutoff, from the perspective of feminist film theory, demonstrates the evolution of women in culture. The female filmmaker, Kelly Reichardt, constructs an indicative anti-western, from its decision to film in the outdated 1.33:1 aspect ratio as well its disinterest in landscapes typical of the genre. The film often places us in the shoes of its women characters, as we peer into the whispering conversations of the men. The desperate struggle for hope manifests itself from the beginning of the film and hangs over the heads of its characters.

Meek’s Cutoff lacks a central hero, another break from the iconographies of the western, and instead charts the progression of Emily Tetherow (Michelle Williams), from a voiceless secondary character into a gun-shielding badass in charge.

4.

A Separation

The dissolution of a marriage in Iran is examined in a novelistic manner with its use of multiple stories (and conflicting accounts), complex and flawed characters, and a societal critique, which extends itself onto a national, then global level. The film finds its strengths in presenting what is essential the same story from multiple sources, asking its audience to continuously shift and assess their identification with its characters. The film unfolds like a piece of great literature, positioning itself as an engrossing melodrama, and it’s remarkable how much is said through character.

5.

Beginners

The romantic comedy genre is more than dead as of now, and somehow there’s still hope, as seen in

Beginners. Mike Mills’ autobiographical film is a film that could have easily been cutesy, but the film comes from a personal place and therefore feels authentic. The film is concerned with an elderly man, portrayed remarkably by Christopher Plummer, who discovers that he is terminally ill. This is also around the same time that he decides to tell his son that he is a homosexual.

Beginners is surprisingly delightful, and you’ll fall in love with Ewan McGregor and Mélanie Laurent, who run into each other during a party dressed up as Sigmund Freud and Charlie Chaplin, respectively. The film also features a talking dog, because, well, it can.

6.

Shame

Steve McQueen abandons some of his precise camera techniques that he used so beautifully in

Hunger, and takes us into the gritty lifestyle of Brandon (Michael Fassbender), a man battling sex addiction. Michael Fassbender’s performance is the best of the year and it’s on brutal display in this film. Shame doesn’t refrain from showing us Brandon’s desperation; he more than hits rock bottom, he’s crashing and burning throughout the entire film. Brandon’s relationship with his sister, Sissy (Carey Mulligan) is a damaged one, which Steven McQueen doesn’t explain, and it’s all for the better. The best thing about this film is that it’s stylish, using repeated music with a sampling of Hans Zimmer’s “Journey to the Line.” The conclusion of the film leaves us with more questions than answers, because sometimes there are no straightforward answers to life’s problems.

7.

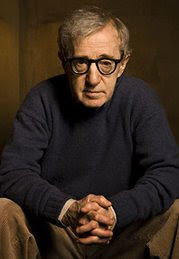

Midnight in Paris

If your film revolves around a man who is nostalgic for a time period other than his own, what’s a better setting than Paris? Gil (Owen Wilson) takes on the Woody Allen character, and does a surprisingly good job, as he roams around the streets of Paris with his fiancée, Inez (Rachel McAdams). Gil, however, who longs to be a writer of great literature, is transported back into time and finds himself in Paris in the 1920s. There are a lot of twists and turns in this film, as well as cheerful surprises. In the film, one of the characters says nostalgia is “a denial of a painful present,” and that’s oh, so true, for some of us. The opening sequence of the film is a nod to Woody Allen’s own Manhattan, while the ending is one of his most touching endings since Hannah and Her Sisters.

8.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s police procedural film is given the epic treatment, both because of its 150 minute running time, and also because of its bold, assuming title. The film centers on a search for a dead body in the Anatolian steppes, and much of the film depends on the atmosphere and tone the film so successfully creates. There’s a sense of dread and mystery that drives the film, and the audience is asked to participate in the grueling, and at times, desperate and helpless search. The film is split into two parts; the countryside and the city, and they’re separated by a beautiful intermission that takes place in the village. Nuri Bilge Ceylan channels Andrei Tarkovsky and Michelangelo Antonioni throughout the film, both in terms of its use of visuals and character.

9.

Weekend

I haven’t seen a love story all year that was as convincing as

Weekend, and that’s also considering the usual clichés that come with love stories. In the film, Russell (Tom Cullen) meets Glen (Chris New) in a club, and the two men spend an entire weekend together. The film focuses on their time together, as well as some time apart, and is more concerned with everyday life details rather than an overall story. This film is an accurate portrayal of love and all its heartaches, with two of the best performances of the year from two emerging actors. The ending of the film will break your heart, and make you realize that love is a precious thing, regardless of sexuality.

10.

Hugo

Martin Scorsese’s

Hugo, a family film in 3D, is surprisingly one of his most personal films. The film centers on the title character, a young orphan who lives in the walls of a train station. In some sense, this film epitomizes the magic of cinema; films are like adventures, we hand ourselves over to the filmmaker and ask him to take us on a ride, and that’s precisely what this film does. The film is shot in color, widescreen, and 3D, but somehow captures the essence of the origins of cinema. The young orphan stumbles upon Georges Méliès, and from there, the film presents us with the history of cinema, as well as the importance of preserving that history. Martin Scorsese, who is nearly 70-years-old, has made his boldest film and shows us how adventurous life can be, only if we allow ourselves to participate in the journey!